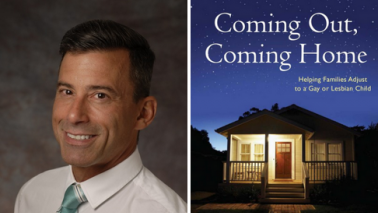

A Conversation With Dr. Michael LaSala, Ph.D. — Part 1

A Conversation With Dr. Michael LaSala, Ph.D. — Part 1

by Erin McKissick

Erin McKissick recently had the opportunity to talk with Dr. Michael LaSala, an associate professor at the School of Social Work at Rutgers University and a practicing psychotherapist and teacher/trainer. Our conversation touched on a variety of topics, ranging from Dr. LaSala’s book, which details the findings of a qualitative study of 65 gay and lesbian youth and their families, to the therapy work that he does with religious families of LGBT children. We are presenting his thoughts in a two-part article to be published during the month of January. Part One focuses on parents’ reactions when a child comes out, and goes over some options for how parents can negotiate their feelings during this time. Part Two focuses more on issues of faith and how parents can approach their religious beliefs while loving an LGBT child. We are incredibly grateful for the opportunity to learn from Dr. LaSala and his breadth of knowledge about LGBT youth and families!

We’re very curious to hear about the research that led to the creation of your book, Coming Out, Coming Home: Helping Families Adjust to a Gay or Lesbian Child, which was the result of your qualitative, multicultural study of 65 gay and lesbian children and their parents. In the context of your research, what did you find to be the most common negative feelings that parents deal with when their kid comes out?

Well, there are three main reactions that I have found to be quite common, both in my research and my clinical practice. The first is guilt, and this is the toughest one to deal with because when a parent feels guilty, they are also most vulnerable to having mental heath symptoms, such as symptoms of depression or anxiety. Now of course, parents and particularly mothers often feel guilty over their children, whether they’re gay or lesbian or straight; it almost seems like guilt comes with the parent license and especially with the mother license, like it’s just part of the job. However, I think that this guilt can certainly be aggravated and amplified in a parent when their child comes out as LGBT, because the parent is thinking “What did I do wrong?” In the 1950s, some psychiatrists were surveyed about their gay and lesbian patients in an attempt to determine the psychological cause of sexuality, and this research essentially led to the idea that sexuality is family-generated. Now of course this research was very flawed in terms of bias, because you’re asking people who deal with troubled gay and lesbians for their opinions about homosexuality, so it has since been soundly debunked. However, the idea that parents and faulty parenting can cause homosexuality remains in our narratives about this, and I think it relates to parental guilt. Despite the recent progress on certain LGBT issues, such as the repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell and progress with same-sex marriage being legal in more states, being LGBT is still stigmatized, and by association I think being a parent of an LGBT child is stigmatized. So I think that this stigma also relates to the guilt parents initially feel and are so troubled by when they first find out that their child is gay.

The second common reaction is a sense of grief or mourning. When a parent gives birth to a child, they project all sorts of expectations onto that child, and these projections take for granted that the child is going to grow up to be heterosexual. The projections can be rather gendered, as well, which is a separate issue but often related to heterosexuality. So I know mothers who, when they have a daughter, think that they’re going to be very close. You know, there’s that expression “A son is a son till he takes a wife, a daughter’s a daughter the rest of her life…” So there’s this idea that a mother and daughter will share many common experiences such as being a mother and a wife, and that they’ll be able to share some special moments that a mother couldn’t have with her son. And so when they find out that their daughter is a lesbian, they believe that these dreams are shattered, that these expectations and hopes are no longer compatible, and that somehow the child is picking a lifestyle that is foreign, or something that the parent can’t relate to. So there’s a sense of mourning the heterosexual child they expected to have. I’m currently working with a mother for whom this is all pretty new and fresh and raw, and she becomes tearful when she thinks about her college-age son as a little boy because she’s thinking about what her expectations were when the child was younger. So for her this has been a real transformation, and as with most transformations, there’s a death involved—the death of the idea of the child as heterosexual. Parents will also say that they always dreamed of being in their child’s wedding or having grandchildren, and the idea that an LGBT child can still get married and still have children is cold comfort to parent who were really envisioning something more traditional for their children.

The final typical reaction of parents when their kid comes out to them is that of worry and concern. Even when parents get to a point where they are adjusted and they feel like the experience has made them stronger and closer with their children than ever before, they still worry for them. I think worry is another part of parenting that occurs no matter what kind of child you’re parenting or who your child is, but again, one that may be aggravated for parents of LGBT children. This happens especially when parents become aware of the heightened risk of mental health symptoms in LGBT children, and of the stigmatization and discrimination that LGBT kids face; they’re understandably worried about this. This is all especially problematic for parents who have a lot of social distance from the LGBT community, for parents who don’t know anybody beyond perhaps a suspicion that a co-worker or an acquaintance might be gay. So when parents aren’t aware of the community, they tend to focus only on how much harder their child’s life could be, and they think that their kid will be lonely or depressed or just slogging through discrimination and stigma for the rest of their life. Parents also invoke the names of Matthew Shepard or Tyler Clementi, and worry about their kid when they know that being gay makes them a target. Now as somebody who is openly gay and has been out for over 30 years, I can tell you that what these parents are missing out on are the benefits of being gay, and the fun that comes along with it, and how it gives you a real opportunity to connect with a special community of people that you can find all over the world. These parents who are not yet connected to the LGBT community also don’t see the perspective that being a gay or lesbian person provides, this kind of critical consciousness. On the flipside, even parents who are connected to the LGBT community may be those who lived through and experienced the worst part of the HIV epidemic, the part where people were dying within less than a year, where there was no medicine, and so forth. So there’s another cause for worry or concern that their child will be unsafe.

For parents who may find themselves experiencing these kinds of reactions or dealing with some of the emotions that you spoke about, would you recommend that they go to counseling or therapy for guidance?

You know, I never like to say that therapy is appropriate for all parents. It can certainly be helpful, but I think there are so many different ways that people can deal with this. However they choose to do it, parents need to get educated and find support, and this can even be from within their social networks. Only a small minority of people in my research have gone to therapy, and most of them just found the support of others who enabled them to express their feelings and start to develop a critical consciousness about some of their ideas.

Parents can also do this by going online, for example, to the PFLAG site. Now not everybody is a good candidate for PFLAG meetings. Sometimes it can feel very isolating if a parent is grieving and they attend a meeting where the atmosphere isn’t validating these feelings of grief, and instead is urging them to just “snap out of it” and accept their child. For many, PFLAG meetings are great, and when people can meet others who were in their position and got through it and seem happy and still love their kid, this can be extremely helpful, but depending on the PFLAG chapter won’t be everyone’s experience. However, I refer everybody to PFLAG.org—there’s lost of terrific literature there and plenty of good information. If the family is Catholic, Fortunate Families also has an excellent site. The important thing is that parents work on it and trying to develop resources, whether this is done with a therapist or by confiding in a friend or going online. The problem really develops when people get stuck and say “This is how I feel and I’m not going to change.”

Michael C. LaSala, PhD, LCSW is associate professor at the School of Social Work at Rutgers University and has been a practicing psychotherapist and teacher/trainer for 30 years. His research and clinical specialties are the couple and family relationships of gay men and lesbians. Dr. LaSala’s book entitled: Coming out, coming home: Helping families adjust to a gay or lesbian child (Columbia University Press) describes the findings and practice implications of a National Institute of Mental Health funded qualitative study of 65 gay and lesbian youth and their families. Other examples of Dr. LaSala’s work can be found in over 25 journal articles and his blog for Psychology Today. Dr. LaSala is a much sought after speaker on gay and lesbian couple and family issues and has recently presented workshops, keynotes, and plenaries in Sweden, Canada, Finland, Estonia, Italy, and throughout the U.S.. Further information on Dr. LaSala’s work can be found on his website.

Want to become a volunteer writer? Tell us here!

Austen Hartke's new book shows the world that transgender Christians have always existed, and is an incredible resource to help Christian parents, leaders, and community members understand how trans folks experience Christianity.